Open plan work environments. Often touted as superior when compared to private work areas and offices not only because of the reduction in costs of accommodating staff, but also because of the open collaboration, communication, social interaction and team building they apparently foster.

But does any of this actually stack up? Shouldn't we be looking at empirical studies to determine whether or not the perceived benefits are grounded in truth and reality rather than swallow our gutful of marketing speak about the so-called benefits? Are the cost savings economically sound?

In this article I'll try to appeal to your common sense, logical reasoning and empathy, and will employ such tactics as scepticism, derision, sarcasm and flat out cynicism to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt the ultimate conclusion on the matter. I will conclude the piece with some sobering and indisputable truths. Shall we get started? Rhetorical.

“Open plan”. Words that make an introvert cringe and an extrovert jump for joy and then talk at someone about it for the next ten minutes preventing you from thinking straight and therefore getting any work done1.

Ah, knowledge work. Software engineering, design, development, programming, whatever you want to call what we do, it all requires at least a small amount of concentration and as little cognitive distraction and annoyance as is practicable (particularly visual and aural). Great. Oh yeah, a bit of respect for the knowledge, difficulty and professionalism of our trade wouldn’t go astray either.

The Argument for Open Plan Work Spaces

To get this big ball of mud rolling, I’ll quote from an article titled: Productivity Hacks: The Open Plan Office.

I have always insisted on having an open plan office. It makes things so much easier when you can simply get up and walk over to a colleague if you need to discuss something. Ideas flow a lot more freely…

I couldn’t agree more! Unwanted distractions and careless ad-hoc interruptions are a sure-fire method of boosting productivity. Actively prohibiting flow is a small price to pay for such productivity gains. Oh, unless he literally means to chop his productivity down with rough and indiscriminately blows? Hmm.

Alice: "Hey, I just sent you an email".

Bob (still incoherent after being suddenly jolted out of his code trance...): "I had a complete state machine in my head that took a good 30 minutes to craft and in one fell swoop you have smashed the stack. What was it you wanted again?".

Alice: "Never mind, it's all in the email".

“Productivity Hacks”… I’ve noted that one in my diary for the next corporate dinner I’m invited to. Should definitely turn some heads!

Next up: Agile for the Introvert, because it is only introverts who selfishly think that without great solitude, no serious work is possible.

First, the bad uncomfortable news: Sometimes there is absolutely no substitute for a good ol’ fashioned Agile bullpen. You’ll be better off if you accept this now. While (as an introvert) this is usually the last thing on Earth that I want to do, there are situations that demand it. If you’re up against an important deadline delivery, then you know that you need all the communication bandwidth you can get. Sometimes it’s easier to just have everyone in a room, stand up, shout out the latest critical changes, kick off the integration build, and move on to the next thing. (Where I come from, we call this “Thunderdoming.”)

“Thunderdoming”… another entry for my corporate dinner diary. Thanks!

Oh the joyful imagery this creates in my mind. I’ve always wanted to do intricate work in the middle of an old fashioned stock exchange with people “shouting out the latest critical changes”. Critical changes requiring concentration and some level of intelligence and thought in a rowdy stock exchange type arena. I guess the philosophy naturally extends to having physicists trying to crack out some string theory equations or multi-polarization of qubits proofs all packed into an open area with random people standing up and shouting random equations and theorems. I suppose brain surgeons, watch makers, and all manner of other knowledge workers would all benefit from this arrangement too. Working with this person would be epic.

Now on to a fine piece of generalisation: Do Successful Programmers Need to Be Introverted?

Pair programming is a bit of a pipe dream for most organizations, but if you have gregarious developers who talk to one another, they will at least understand what is going on in each other’s development trees. That means, also, working in group settings. It doesn’t have to be in the office all the time. Some deep code changes require getting away from all distractions for a bit, but if the results of that deep dive don’t come to light in the group, the knowledge only lives in the mind of the hermit and doesn’t ever benefit the organization as a whole.

Systems design? Architecture? Nope. Algorithms or systems integration? Never. I don't even write code, no. I just change it sometimes, and sometimes I even get to make "deep code changes". Of course, as a software engineer I go deep so very rarely that we need to call this sort of specialised and rare occurrence a "deep dive". Upon return we must broadcast to "the group" what we did on our little self indulgent sabbatical because you know, it'll live in our heads because we're hermits and no one actually writes documentation, creates coherent code, comments their work or uses those wiki/issue tracking/version control thingies, do they? Of course, the rest of our work can be done amongst distractions.

Having been so thoroughly enlightened by this article, I haven’t the slightest clue where the concept of “code monkey” and “interchangeable cog” come from. Obviously the author has a lot of respect for developers.

Alice: “Where’s Chuck?”.

Bob: “He’s changing some code”.

Alice: “Hermit!”.

Cheers for the excellent corporate dinner diary entry: “deep dive”.

The Argument against Open Plan Work Spaces

In 1998, a study by Banbury and Berry2 found that all background noise, even in the absence of speech, had a significant negative impact on ability to do mental arithmetic and on memory. Coffee grinders, mobile phones, keyboard tapping, mouse clicking, you name it, even in the absence of speech or even any visual distraction is detrimental to mental acuity.

OK, so noise is a problem, that’s now clear from the studies, so why not just isolate yourself in a pair of headphones and crank some metal? Well, many people retreat into a pair of headphones and listen to music to try to block out all other auditory distractions. Unfortunately, Furnham and Strbac3 show this is detrimental to cognitive performance too (but at least to me, more tolerable than the yakity yak!).

Sundstrom et al.4, showed as far back as 1980, that privacy afforded by architecture is directly correlated with one’s feeling of psychological privacy which in turn was shown to be directly correlated with higher workplace performance and career satisfaction. Openness, it was concluded, was directly related to increased disturbances and decreased privacy. Most negatively affected were those with the most demanding roles as, what comes as no surprise, those roles require peace, privacy and lack of interruption in order to perform at the required level. Not surprising but worth noting nonetheless, is that no matter the role of employee, the overwhelming preference was for private working conditions, and the performance of even “non-complex” roles saw increased productivity when afforded privacy.

In a study of employees from a Canadian oil company conducted by Brennan et al.5 called Traditional versus Open Office Design: A Longitudinal Field Study in 2002 it was concluded that on the subjects of work place satisfaction, self assessment and relationships with other workers, the overwhelming perception of the employees was negative towards the open plan concept that replaced their previous private work spaces.

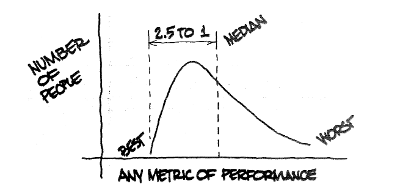

In the classic book Peopleware, Tom DeMarco describes in detail a long running study, started in 1977 called “Coding War Games: Observed Productivity Factors”. From 1984 to 1986, more than 600 developers from 92 companies have participated in these games. In this study, participants compete against each other on an identical software engineering task, designing, coding, and testing a medium-sized program to spec, recording the time spent on tasks in a log as they go. Once the projects are complete they are subjected to acceptance testing.

The subjects work in their normal working environments, for their regular hours, using the same tools. languages and computers they would normally use for their regular project work.

The top quartile, those who did the exercise most rapidly and effectively, work in space that is substantially different from that of the bottom quartile. The-top performers’ space is quieter, more private, better protected from interruption, and there is more of it.

So, as argued by Tom DeMarco: is it the quiet privacy of workplace that produces such stark differences? Is it just the fact that the brighter people gravitate towards companies and institutions that provide such private and quiet work spaces? Is it a combination of the two?

Why care? If it 1) dramatically increases the productivity of your current employees, or 2) attracts better employees to your institution then both are reasonable and sane things to do which not only provide greater psychological benefits for your employees but also produces a better bottom line through productivity, quality and efficiency.

Conclusion

I know some great developers who can design beautiful and succinct systems, integrate disparate bits of hardware with efficient software to create seamless products, hammer out robust, coherent and understandable code and software systems, both within teams and by themselves when afforded a little peace. Yet, these same people fail to function at a third of their ability in the maelstrom of movement and cacophony of yakking about what we’re having for lunch, kids and weekend activities that we sadly call an office these days. In what other alternative universe would it be acceptable to prevent the intricate knowledge work of a professional taking place in order to promote “collaboration” and “team work” and to save a few bucks on the side? It’s clear that the few who make noises about these issues (those targeted in the introductory quotes) are just the few that recognise a problem that affects all developers whether or not they like working in an open plan anti-pattern. Is the open plan office economically sound? It’s overwhelmingly clear that it is not.

To wrap this up, I suggest we look at an open door policy rather than an open office policy, and shall leave you with one final piece of advice from A Stroke of Genius: Striving for Greatness in All You Do:

Some people work with their doors open in clear view of those who pass by, while others carefully protect themselves from interruptions. Those with the door open get less work done each day, but those with their door closed tend not know what to work on, nor are they apt to hear the clues to the missing piece to one of their “list” problems. I cannot prove that the open door produces the open mind, or the other way around. I only can observe the correlation. I suspect that each reinforces the other, that an open door will more likely lead you and important problems than will a closed door. – R. W. Hamming.

I’d love to debate this topic further with you so please indulge me with your comments!

Notes

-

I’ve got nothing against extroverts, honestly, after all, they need peace to get great work done too. Besides, some of my best friends are extroverts. ↩

-

Reference: Banbury and Berry, “Disruption of Office-Related Tasks by Speech and Office Noise” (British Journal of Psychology, 1998) ↩

-

Furnham and Strbac, “Music Is as Distracting as Noise” (Ergonomics, 2002) ↩

-

Sundstrom et al., “Privacy at Work: Architectural Correlates of Job Satisfaction and Job Performance” (Academy of Management Journal, March 1980) ↩

-

Brennan et al., “Traditional Versus Open Office Design” (Environment and Behavior, May 2002) ↩